The L-shaped Middle Ground Shoal sits in the middle of major shipping lanes just off the coast of Hampton Roads, Virginia. In addition to the nearby Navy base, commercial ports, shipyards, and dry-docks, this location is also famous for the first battle between two ironclad warships, the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (Merrimack) during the American Civil War in 1862.

CONSTRUCTION

In 1887, the Lighthouse Board identified the need for a lighthouse at Newport News Middle Ground Shoal in its annual report:

"Vessels leaving the docks at Newport News drawing 24 feet of water invariably pass to the southward of the Middle Ground, and because of the several changes of course, masters now hesitate to leave their berths for sea on very dark or foggy nights. To obviate the necessity for thus losing much valuable time a light-house and fog-signal should be established on the Middle Ground, near Newport News, or in the vicinity of Newport News at such a point as may be selected by the Board."

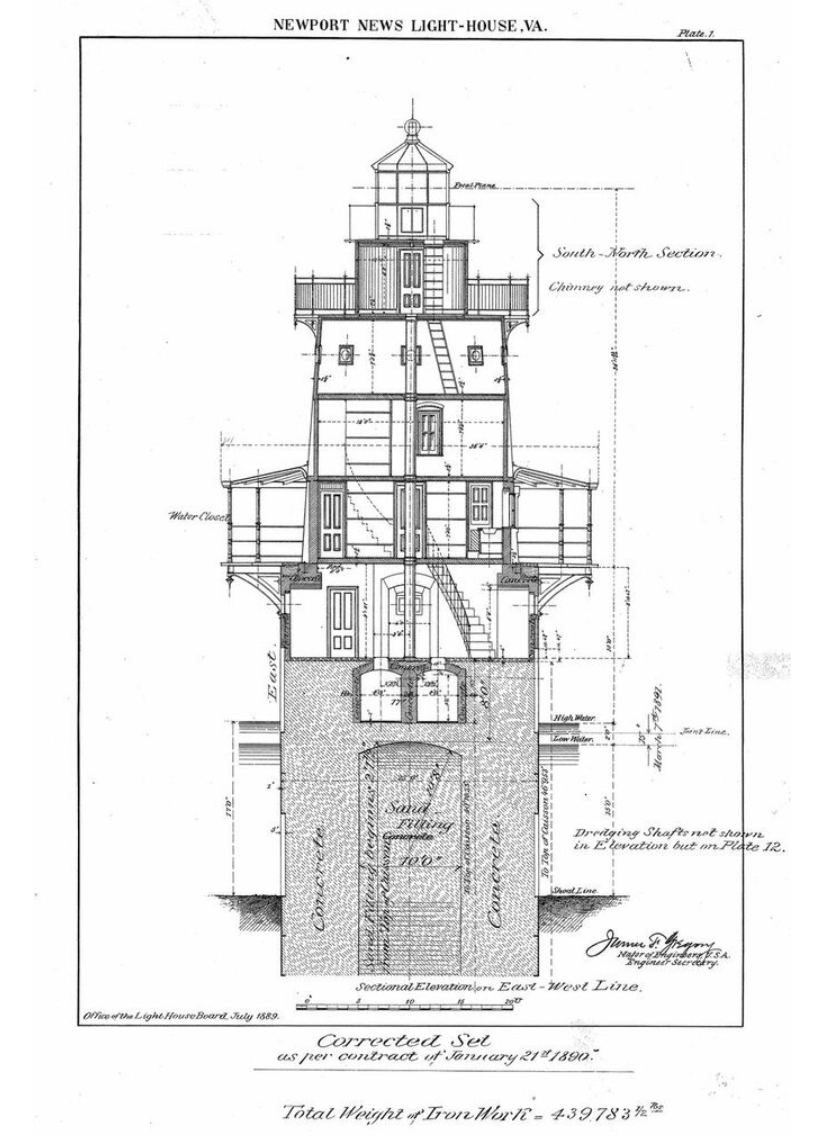

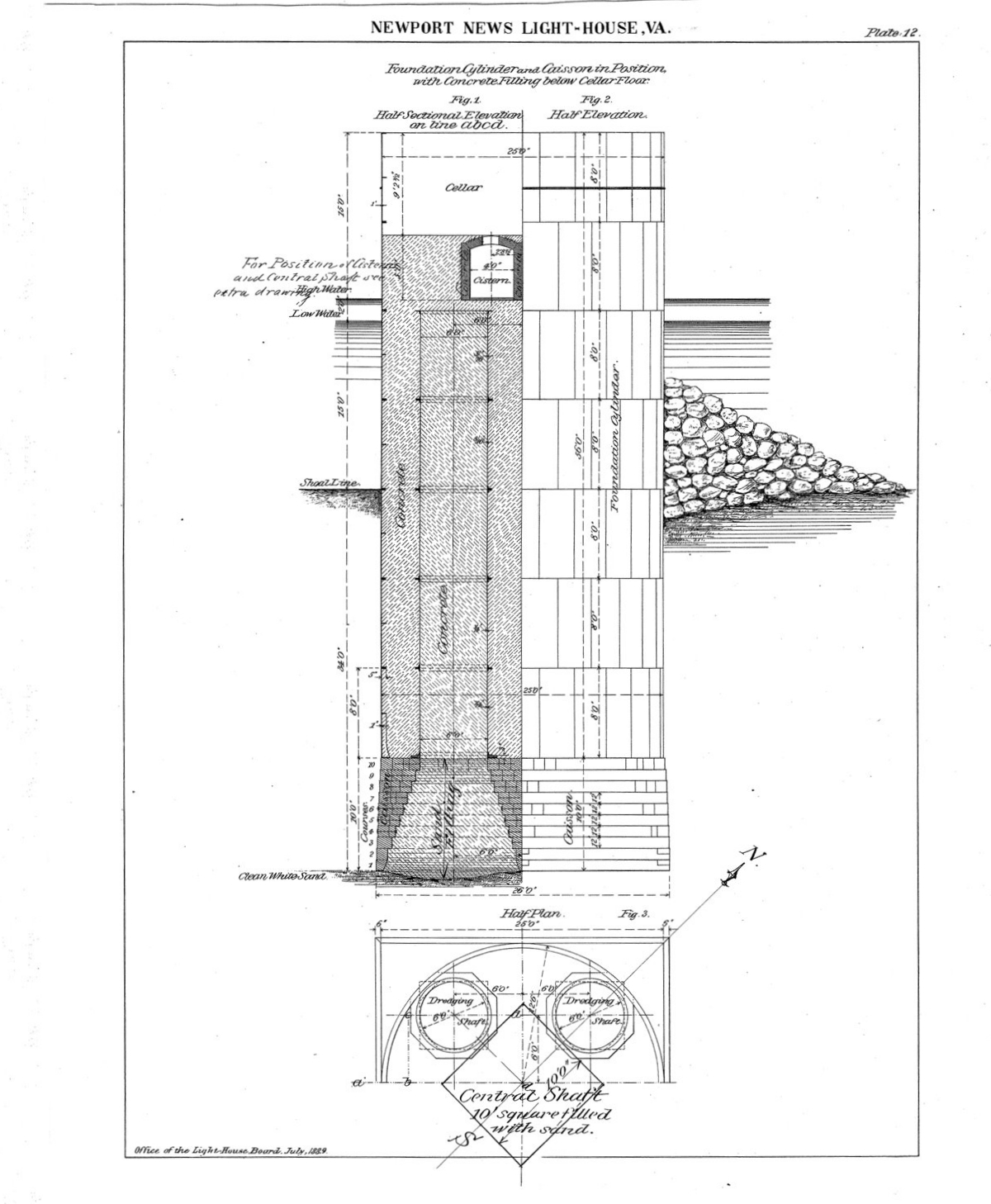

The following year, Congress appropriated $50,000 for its construction. Bid proposals were requested, but the lowest bid left too small of a margin for the purchase of necessary materials and other incidental expenses. The Lighthouse Board then cut a few corners, “...modifications, which would not impair its stability, were made in the sub-structure, the quantity of riprap stone (to be distributed at the base of the caisson) was reduced one third.” With these alterations, the contractor was able to lower his bid by $4,000 and began the project in the spring of 1890.

The Board reported that over the summer of 1890, "the framing of the crib was commenced at Newport News, Virginia...the iron caisson was delivered at the Portsmouth, Virginia depot, and... the iron superstructure is nearly finished at the contractor's shops." In July, "the wooden caisson with four sections of the dredging shaft and two courses of the foundation cylinder was towed to the site and sunk." By October, the caisson had dropped to the layer of clean, white sand 34 feet beneath the top of the shoal. In January of 1891, the iron tower was complete, and on "April 15, 1891, the light was first exhibited from the lens for the benefit of mariners." It was a fixed white light accompanied by a white flash every twenty seconds.

STRUCTURE

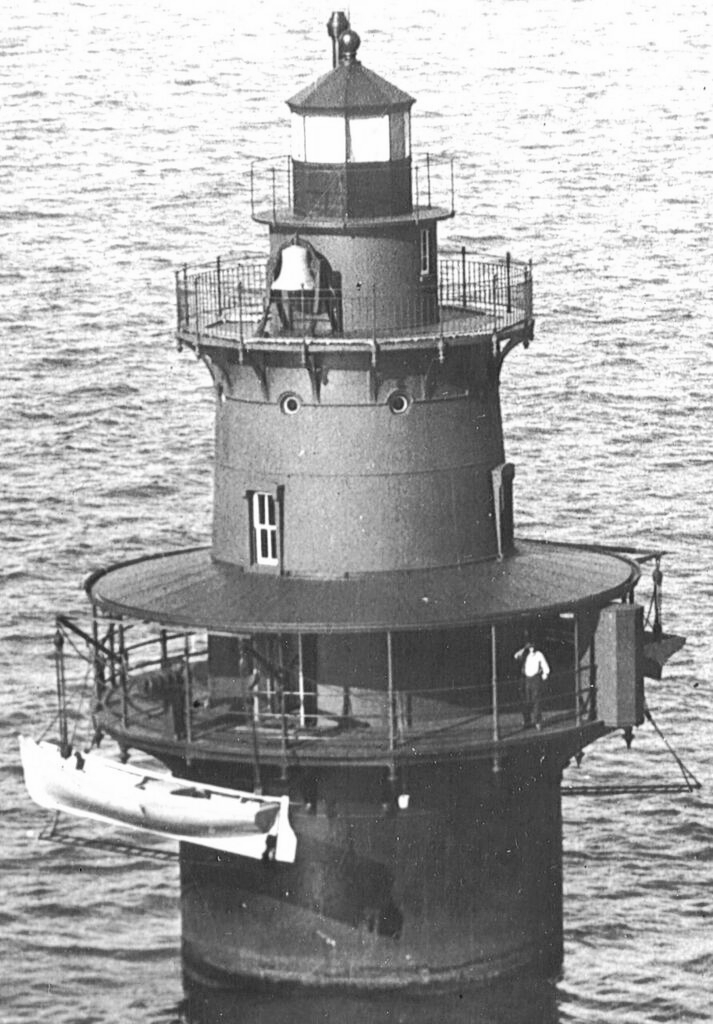

An examination of Middle Ground Shoal determined that it “is composed of sand and clay until, at 34 feet in depth below the surface of the bottom, perfectly clean white sand is reached. There is, therefore, no doubt about the suitability of the foundation.” However, the Board had learned from its past use of screwpile lighthouses that rough seas and winds can cause problems for offshore structures. Inspectors were concerned about the water’s depth at the site, which was 21 feet at high tide. Deep water is more heavily trafficked, and the position of Middle Ground Shoal would expose the lighthouse to the danger of being run into by both steam and sailing vessels. During winter, it would also be exposed to shocks from fields of running ice. The Board decided not to risk another screwpile beacon being rammed by ships or carried away by ice floes; only a strong iron caisson foundation would be considered, thus a “sparkplug" or "coffee pot” design was chosen. Middle Ground is only one of 33 remaining sparkplug lighthouses in the country; you can find more information on them here.

The lighthouse's caisson foundation is 56 feet high and 25 feet in diameter, and is visible 15 feet above the water level. The caisson was originally painted black, and the conical tower that tops it was brown in color. The tower is 29 feet high and 21 feet in diameter at its base; its light sits an average of 51 feet above the water. The lighthouse was originally equipped with a Stevens fog bell, which was sounded twice automatically every fifteen seconds.

The lighthouse has five levels, beginning with a cellar, which is actually 9 feet above sea level. It has brick walls and a concrete floor, where rain collecting cisterns gather the runoff from gutters along the first level roof. The main level walls are lined in brick with floors made of unpainted tongue and groove heart pine boards. Sleeping quarters are on the next level, followed by a floor originally for equipment, and finally a watch room with an iron floor and tongue and groove wooden walls. An iron ladder ascends through the ceiling of this level, leading to the octagonal lantern room.

Deterioration & improvements

The station was automated in 1954, at which time the light and fog bell were altered. The light flashed a white 3,000 candlepower every six seconds, and the fog bell sounded one stroke every fifteen seconds, instead of two. The lighthouse was also downgraded along with these changes; the Coast Guard reclassified it as a "second class tall nun buoy." The Coast Guard terminated the direction calibration service at the station, and unnecessary equipment including the station boats were removed. The light was to be operated using batteries, and these needed to be changed every nine days. This proved a difficult undertaking, as the iron ladder descending from the first level deck 'reverts' itself, and maintenance crews embarking from their boats had to swing around to the opposite side of the ladder after climbing up the first ten feet.

In 1982, the first major inspection team investigated the lighthouse, with an eye to possible repairs. What they found was alarming: sections of the balustrade were missing from the gallery deck, holes had appeared in the gallery roof, and pieces of the first level decking had been torn away by an errant ship in 1979 so that water leaked into the foundation. A perusal of the cellar revealed flaking paint and leaky porthole windows, and the cisterns were filled with water that might have come from the compromised foundation. On the first, second, and third levels was more flaking paint and leaking windows, along with ubiquitous seagull eggs and droppings. The watch room and lantern room were missing windows and had broken, wide open doors, granting birds free access to nest near the light.

Some repairs were made, and in 1987 solar power was installed at the station. Two twelve-volt batteries were placed on the floor of the lantern room, and the light was moved outside to a pole above the gallery. In 1988, the Coast Guard spent $14,400 on a long list of improvements, including sandblasting and painting, replacement railings, and a new and safer access ladder. In 1992, however, an inspection found that iron plates of the tower were rusting away and water was still leaking into the caisson. These observations were confirmed in 1994 when inspectors noted pitting rust all around the waterline of the foundation, and “considerable rust” up and down the seams of the tower’s plates. Corrosion had also attacked the new access ladder and the underside of the first level deck.

The state of disrepair even extended to the maintenance logs themselves, which were missing. The inspector’s report made some practical suggestions to immediately improve the lighthouse. It recommended moving the light from its exterior pole back inside to the lantern pedestal, making it easier to service. The report suggested replacing the age-yellowed lantern panes and changing out the steel plates over the windows with vented acrylic glazing to improve air flow in the structure. The inspectors decided it would be best if qualified sub-contractors addressed the structural instability in the main deck and foundation.

After the opening of the nearby Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel in April 1992, the Virginia Pilot Association, which is responsible for guiding ships into and out of the harbor, asked for more changes to the light. The white light was blending in with lights from the bridge and coal piers behind it, so for the first time in its 109-year history, the light was changed to red and made much brighter.

LIGHTHOUSE KEEPERS

James B. Hurst (Head 1891)

Daniel J. Clayton (Assistant 1891, Head 1891 - 1894)

E.M. Edwards (Assistant 1891)

George E. Evans (Assistant 1891 - 1892)

John A. Cornick (Assistant 1892 - 1895)

Charles F. Hudgins (Head 1894 - 1898)

John F. Hudgins (Assistant 1896 - 1899)

James E. Lewellen (Head 1898 - 1904, Assistant 1915 - )

Alpheus B. Willis (Assistant 1899)

Mumford Gwynn (Assistant 1899 - 1900)

William C. Simpson (Assistant 1900)

Charles Berry (Assistant 1900 - 1901)

Frederick Farrell (Assistant 1901 - 1902)

Edward Farrow (Assistant 1902 - 1907, Head 1908 - 1917

Rufus Hunley (July 17 - July 18 1917) only one day!

Wesley F. Ripley (Head 1904 - 1906)

John F. Jarvis (Head 1906 - 1908)

Henry E. Ratcliffe (Assistant 1907 - 1908)

Charles O. Perl (Assistant 1908 - 1909)

V.J. Montague (Assistant 1909 - 1910)

Charles Vette (Assistant 1910)

Edward D. Parham (Assistant 1910 - 1911)

James T. Parks (Assistant 1911 - 1912)

Thomas J. Cropper (Assistant at least 1913)

George C. Johnson (Assistant - 1915)

B.F. Bradshaw (Assistant 1915)

John E. Stubbs (Assistant - 1917)

Carl G. Marsh (Assistant 1917 - 1918)

Malachi D. Swain (Head 1917 - at least 1920)

Martin B. Tolson (Assistant at least 1919 - at least 1920)

Henry H. Twiford (Assistant at least 1921)

Homer T. Austin (Head at least 1921)

William A. Gibbs (Assistant 1927 - 1928, 1938 - 1944)

Arthur M. Meekins (Head 1928 - 1940)

Edward B. Austin (Head 1941 - at least 1942)

Billingsley & Gonsoulin Families (2005 - Present)

AUCTION

In 2000, Congress passed the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act, which provides a mechanism for the disposal of Federally-owned historic light stations that have been declared excess to the needs of the responsible agency, while still recognizing the cultural, recreational, and educational value associated with historic light station properties. The NHLPA led the Coast Guard to put four Chesapeake Bay lighthouses up for sale in 2005, as they were too expensive to maintain. Bob Gonsoulin and his wife Joan, along with her sister Jackie and husband Dan Billingsley, purchased the lighthouse with a final bid of $31,000.